This quote has been swirling through my head lately, especially when I encounter advertisements for the latest hyper-hybrid, monster-blooming shrub or perennial. The Proven Winners plants, for example, have become the Barry Bonds of nursery plants. Or what’s worse, now we have celebrity gardeners like P. Allen Smith’s who have trademarked their own laboratory-bred Platinum Collection plants. The American horticultural industry seems bent on producing engineered plants that bloom eternally. Mophead hydrangeas no longer mark the beginning of summer, thanks to the Endless Summer Hydrangeas (trademark). Encore Azaleas promise blooms spring, summer, and fall. What does a fall blooming azalea mean, anyways?

Of course, there’s nothing wrong with loving big flowers. Just this week, I passed a neighbor’s peony border with softball-sized magenta blooms. It was glorious. But a garden with nothing but genetically-engineered super-bloomers is a like inviting only models to a dinner party. When prettiness trumps character, we all lose.

Which is perhaps why this year I have been seduced by an ancient family of plants. During some deep winter garden reading, I started to make connections between several bizarre, yet fascinating plants. Turns out, they all belong to the remarkable nightshade (Solanaceae) family. Plants of the nightshade family are the perfect antidote to overly-bred bloomers. First, most of these plants are anything but pretty. This year, I’m growing the rather grotesque Naranjilla plant (Solanum quitoense). It is a nasty looking plant: its massive leaves are covered with deep purple spikes. This ancient Incan plant produces little orange fruits that I understand taste like a cross between rhubarb and lime.

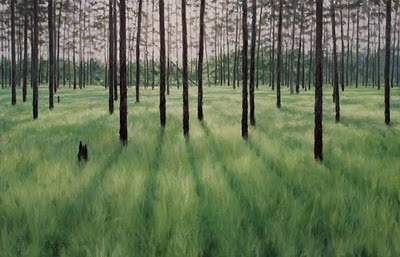

Solanum quitoense in a mixed border [image from Landcraft Environments LTD]

Perhaps the dark and dangerous history of these plants is what makes this family so seductive. While some of the plants create the most nourishing comfort foods on the planet, others are downright deadly. Snakeberry (Solanum dulcamera) has egg shaped red berries just like a cherry tomato that contain high levels of the phytochemical solanine. Solanine is known to cause birth defects, hallucinations, convulsions, fits of laughter, coma, and even death. Even potatoes and tomatoes contain small levels of solanine. Other nightshades contain tropane alkaloids. The term tropane is named after the Greek Fate, Atropos, who cut the thread of life. Tropane alkaloids are found in nightshade ornamentals like Datura and Brugmansia.

Like living dangerously? Several respectable seed sources sell Garden Huckleberry (Solanum nigrum var. melanocerasum), a variant of the deadly nightshade. Several regions of our country make jams and pies from the berries of this plant. Be careful though: others claim this plant causes defects of the central nervous system. Want to play it safe, but still explore the wonderfully bizarre world of nightshades? Try the Pepino Melon (Solanum muricatum), a compact South American shrub that produces fruit the size of a large goose egg. Beautifully pendulous cream colored fruit has purple stripes. The fruit has sweet, mild flesh that is somewhat melon-like.

Nightshades are a reminder that there once was a time when plants could strike fear in the human heart. This year, I passed on the goopy Endless Summer Hydrangea and instead planted a nasty looking Naranjilla. It’s massive leaves studded with purple spikes greet me each morning, a reminder that out of fear and understanding, comes respect.

Want seeds of some of the plants mentioned?

Baker Creek Heirloom

Top Tropicals